In the first part I showed how the Sinclair ZX Spectrum stored data on tape. This second part explains what is stored, and what causes a tape loading error.

In the first part I showed how the Sinclair ZX Spectrum stored data on tape. This second part explains what is stored, and what causes a tape loading error.

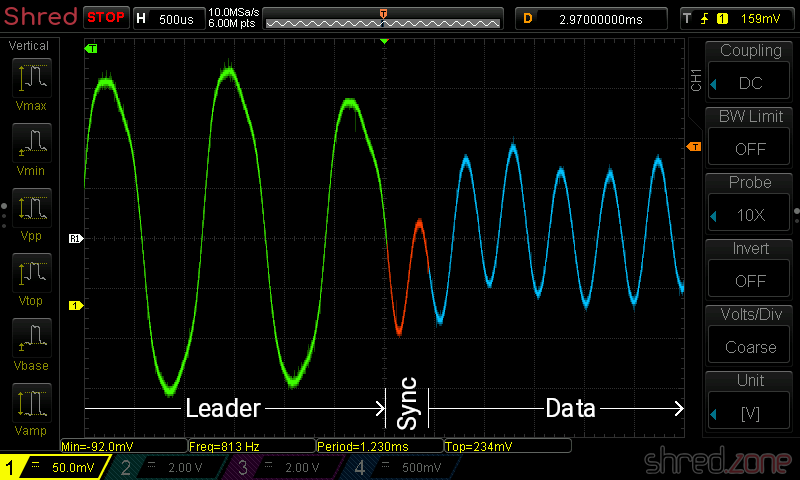

The ZX Spectrum BASIC offers a SAVE command for saving all kind of data. It can be used to save a BASIC program, variable arrays, but also arbitrary parts of memory. These files are always saved in two separate blocks. The first block is called header. It contains the file name, data type, and other meta information. The second block follows about a second later and contains the data itself.

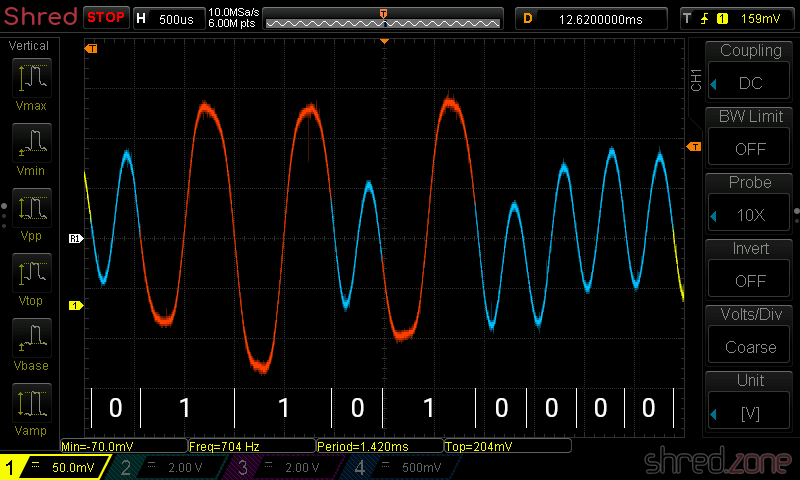

The internal structure of each block is identical. The first byte distinguishes between header ($00) and data blocks ($FF). The final byte is a parity checksum. Everything between these two bytes is the payload.

A header block always contains a payload of 17 bytes. The first byte identifies the file type, followed by the file name (10 characters), followed by the length of the data block, and closed by two optional parameters that have different meanings depending on the file type. The length and the two parameters consume two bytes each, with the lower byte coming first because the Z80 CPU is little endian.

This is an example header block of a screenshot:

00 | $00 = Header | |

| 00 | 03 | $03 = Binary file (Code or SCREEN$) |

| 01 | 53 | S |

| 02 | 68 | h |

| 03 | 72 | r |

| 04 | 65 | e |

| 05 | 64 | d |

| 06 | 2E | . |

| 07 | 7A | z |

| 08 | 6F | o |

| 09 | 6E | n |

| 10 | 65 | e |

| 11 | 001B | Length: 6912 bytes ($1B00) |

| 13 | 0040 | Parameter 1, here: starting address ($4000) |

| 15 | 0000 | Parameter 2, here: unused |

20 | Parity |

A screenshot is actually just a memory dump that starts at address $4000 (which is the starting address of the screen buffer) and is exactly 6912 bytes long (the ZX Spectrum has a resolution of 256×192 monochrome pixels plus 32×24 bytes color attributes, giving a screen buffer size of 6912 bytes).

For other file types, the two optional parameters have different meanings. For example, a BASIC program file stores the line number to start at after loading.

The final byte is the parity. It is used for error detection, and computed just by XOR-ing all the bytes that have been read. The result must be $00, otherwise a "R Tape loading error" is reported.

This kind of error detection is rather weak. Due to the nature of the XOR operation, two wrongs give a right. This means that when the block contains an even number of bad bits at the same position, they will be undetected. It is also not possible to correct reading errors, as the XOR operation only allows to identify the position of the bad bit, but not the actual byte that contained the error. More sophisticated error correction algorithms would have slowed down the loading process, though.

The parity is checked as a final step, after all the bytes have been read from the block on tape. For that reason, the loader can only decide at the end of the recording whether the loading was successful or not.

But then, why does the tape loading error sometimes appear while the block is still loading? Well, in the first part I have explained that the loading routine just reads an unknown number of bytes. It ends when waiting for a pulse change took too long. Now, if there is an audio gap on tape, the signal seems to end just in the middle of the block. It is then very likely that the parity checksum is wrong because there are still bytes missing.

Some simple copy protections made use of the way the Spectrum loads data from tape. A very common way were “headerless” files, where the header block was left out and only the data block was recorded on tape. The BASIC LOAD command was unable to read those files because of the missing header.